Health Centers > Cancer Health Center > Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal Cancer

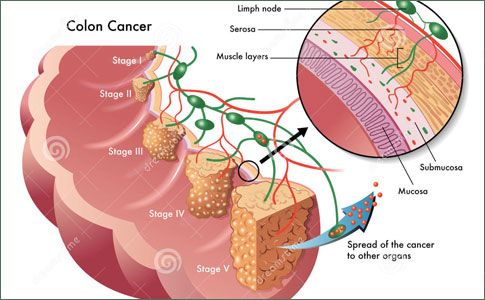

Colorectal cancer (CRC) continues to be one of the predominant cancers in the Western world, surpassed only by lung cancer in mortality rates. It is estimated that 135,400 new cases of colorectal cancer will be diagnosed in 2001 and that 56,700 people will die from the disease during the same period. Despite advances in early detection, screening, and treatment, these mortality figures have remained relatively constant. The fiscal implications of CRC management are staggering, with approximately $6.5 billion spent on CRCrelated care in the United States annually. There are emerging differences in racial mortality rates, with African Americans having the highest mortality rates (50.7 per 100,000 people) compared to Caucasians (43.6 per 100,000 people). American Indians have the lowest incidence (16.3 per 100,000 people). Colorectal cancer affects men and women equally.

Colorectal cancer

Colorectal Cancer definition

Presentation

Risk Factors

Epidemiology

Colorectal cancer Risk Factors

General Considerations

Incidence and Location

Variations in Incidence Within Countries

Anatomy and Pathogenesis

Diagnosis and Screening

Clinical Findings

Differential Diagnosis

Screening for Colorectal Neoplasms

Classification Systems

Treatment

Colorectal Neoplasms Treatment

Prognosis

Follow-Up after Surgery

Risk factors for colorectal Neoplasia

Prevention

References

Advancing age remains the single greatest risk factor favoring the development of CRC. Therefore, the costs of managing colorectal cancer are likely to increase as the population ages. Today Americans have a 5% chance of developing this cancer during their lifetime. Certain risk factors substantially increase an individual's chances of developing CRC: inflammatory bowel disease, colonic adenomas, a family history of CRC, and a high-fat/low-fiber diet. Although the etiology of CRC is not completely understood, environmental, genetic, and dietary factors are believed to be responsible for 85% to 90% of all cases.

There is cause for some optimism, however, as the advent of colonic endoscopy, our improved understanding of the adenoma-carcinoma continuum, and elegant cellular and molecular biologic techniques have made CRC now one of the best models for translating research into useful clinical practice. Improvements in fiberoptic technology and sound screening protocols have made elimination of CRC as a major cause of death a theoretic possibility. Efforts continue toward the development of more effective strategies aimed at early diagnosis and prevention.

Presentation

Variability in the signs and symptoms of CRC poses a significant challenge to the physician. CRC may be asymptomatic, with the diagnosis being made by a CRC screening examination or serendipitously while evaluating the patient for an unrelated illness. For symptomatic CRC the signs and symptoms vary depending on the location of the lesion. Right-sided tumors present most commonly with anemia, abdominal pain, weight loss, or a change in bowel habits. If the lesion is left-sided, the most common presenting findings are change in bowel habits, rectal blood loss, and abdominal pain.

Right-sided colon tumors rarely produce changes in bowel habits but are more likely to be the source of chronic occult bleeding that can lead to symptoms consistent with iron deficiency anemia (fatigue, dizziness, palpitations).

Anal Cancer: Strategies in Management

The management of anal cancer underwent an interesting transformation over the last two decades.

When a postmenopausal woman or adult man develops such symptoms in the absence of an obvious cause, CRC should be suspected. Pain in the lower abdomen is an occasional symptom of tumors located in the transverse or left colon. These patients are more likely to notice a change in bowel habits, as either diarrhea or constipation can occur owing to a constricting lumen. The stool may be dark or maroon-colored, and passage may be associated with bloody mucus. Weight loss and fever are occasionally reported as well but seldom as the sole presenting symptom. The first signs of colon cancer may be produced by metastatic disease. Colon cancer metastasizes to the liver and lung, whereas rectal cancer metastasizes primarily to the lung and bone. An otherwise asymptomatic patient may have pruritus and jaundice due to liver involvement. Ascites, enlarged ovaries, and scattered deposits in the lungs may also result from the otherwise undetected presence of CRC.

Obstruction and perforation are the conditions most often associated with the acute presentation of CRC. Obstruction of the large bowel is highly suggestive of cancer, particularly in older patients. Complete obstruction occurs in up to half of patients, depending on the location of the tumor. Long-term survival rates are poorer for patients who have obstruction at the time of diagnosis. Perforation is a surgical emergency and may precipitate complications such as peritonitis and abscess formation.

Carcinoma of the Anus

Introduction

Epidemiology

¬ Sexual transmission / HPV infection

¬ Immune suppression / HIV infection

Pathogenesis

Clinical features

Staging

Treatment

Anal canal cancer

Anal margin cancer

Anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN)

References

Risk Factors

Polyps

Polyps are a risk factor for CRC, particularly if they are adenomatous in type. Siblings and parents of patients with adenomatous colorectal polyps have a 1.78 relative risk for developing CRC. The age at the time of polyp diagnosis is an important prognostic factor for the risk of cancer development. Siblings of patients with adenomatous polyps diagnosed before age 60 have a 2.59 relative risk for developing CRC. Polyp size and histology are directly related to the risk of CRC, with villous polyps larger than 2 cm having a 50% greater chance of containing cancer than smaller or nonvillous polyps.

There is concern that a small distal colorectal polyp, whether adenomatous or hyperplastic, is a proximal neoplasm marker. In study of 366 patients without a history of CRC or polyps, Pennazio et al demonstrated that 34% of patients with distal small colorectal polyps also had proximal polyps noted on colonoscopic examination. These proximal lesions might have been missed had colonoscopy not been performed.

Familial Adenomatous Polyposis

Familial adenomatous polyposis is an autosomal-dominant disease, with an occurrence rate of 1:7000 to 1:10,000 individuals. The colon is virtually completely lined with polyps. Approximately 50% to 75% of these patients develop CRC by age 35 if colectomy is not performed. Diagnosis is by genetic testing of family members.

Dietary Factors

Dietary fat increases bowel transit time and increases the concentration of fecal bile acids, such as cholic and deoxycholic acid. These bile acids act as potential carcinogens on the colonic mucosa. In contrast to fat, fiber decreases bowel transit time and therefore exposure of the bowel to these carcinogens. Fiber, particularly wheat fiber, has been reported to have a protective effect against the development of CRC. A randomized study of high-dose wheat bran fiber and calcium supplementation reported reduced colonic levels of total and secondary fecal bile acids compared to controls. It is postulated that because bile acids may be carcinogenic, reduction of their concentrations in the colon may be the mechanism by which a high-fiber diet reduces the risk of developing CRC. However, a recent long-term study of 61,463 Swedish women (average 9.6 years of follow-up) revealed no decrease in the risk of colorectal cancer with high consumption of cereal fiber. The study did find that those women who had very low intake of fruits and vegetables had a much higher risk of developing colorectal cancer.

A diet rich in carbohydrates, fruits, and fiber may bestow a strong protective effect from adenoma development, whereas ingestion of a high-fat diet increase the risk of CRC development more than twice that of control groups. Dietary factors also play a role in the development of CRC in individuals who consume alcohol. Men who eat a diet low in folate and methionine accompanied by substantial consumption of alcohol (more than two drinks per day) have a 3.3 relative risk for development of colon cancer compared to individuals who drink less than two drinks a day and who have a balanced diet.

Environmental Factors

Environmental influences exert a definite influence on the development of CRC. Industrialized countries are at a relatively increased risk compared to less developed countries or countries that traditionally had high-fiber/low-fat diets. This point is exemplified by the fact that persons from a low-risk country who migrate to the United States over time develop CRC rates similar to those among native U.S. citizens. This increased rate of CRC is probably directly related to dietary changes that accompany migration (i.e., changing from a high-fiber/low-fat diet to a low fiber/high fat diet).

Carcinoma of the Anus Management

Introduction

Epidemiology

¬ HIV Infection

¬ Human Papillomavirus

¬ Other Causes

Prognostic factors

¬ Tumor Location and Size

¬ Lymph Node Involvement

Staging

Disease presentation

Radiation treatment

Combined modality treatment

Optimum chemotherapy regimen

Optimum radiation regimen

Treatment-related toxicities

Follow-Up

Conclusions

References

Only one-third of patients survive 5 years if nodal metastasis is present. Involvement of the deeper, pelvic nodes results in a 20% 5-year survival rate. Approximately 80% of recurrences occur in the first 2 years after treatment. The majority of recurrences occur near the site of the primary lesion. Seventy-five percent of patients with locally recurrent disease (limited to the vulva) can be salvaged with radical wide local excision. In contrast, patients who develop a groin recurrence are rarely curable, and palliative surgical resection is associated with a high risk of complications.

Smoking and Alcohol

Cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption have been reported to increase the relative risk of an individual to develop colonic adenomas and CRC. The relative risk of developing small adenomas is 3.6 for smokers with more than a 20-pack-a-year history. Alcohol consumption (especially when beer is the alcohol being consumed) increases the risk of developing CRC two- to threefold over baseline. Alcohol consumption and tobacco use are independently related to the risk of developing large colorectal adenomas.

Family History of Cancer

Although frequently neglected, a family medical history is an integral component of CRC risk detection. Cancer family syndrome, an autosomal-dominant disorder, incurs a 33% risk that a patient will develop cancer by the age of 50. Common cancers in these individuals include multiple adenocarcinomas of the colon (especially the proximal colon) or endometrium. Patients who have other types of cancer are at a relative increased risk of developing CRC. If a patient has a first-degree relative with CRC, the patient is at a two- to fourfold increased risk of developing CRC him- or herself.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

There is a substantial increased risk of CRC in patients with ulcerative colitis, with the risk being inversely proportional to the age of onset of the colitis and directly proportional to the extent of colonic involvement. Twenty-five percent of patients with ulcerative colitis develop CRC after 25 years of disease. Crohn's disease is also associated with the development of CRC but to lesser degree than ulcerative colitis. Patients with Crohn's disease may have a 4- to 20-fold increased risk of developing CRC compared to the general population, but this association is less clear-cut than for ulcerative colitis.

References

- Greenlee RT, Hill-Harmon MB, Murray T, Thun M. Cancer statistics, 2001. CA Cancer J Clin 2001;51:15-36.

- Schrag D. Weeks J. Costs and cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer prevention and therapy. Semin Oncol 1999;26:561-8.

- Fry R, Fleshman J, Kodner I. Cancer of colon and rectum. Clin Symp 1989;41:2-32.

- Sandler R, Lyles C, Peipins L, et al. Diet and risk of colorectal adenomas: macronutrients, cholesterol, and fiber. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:884-91.

- Vargas P, Alberts D. Primary prevention of colorectal cancer through dietary modification. Cancer 1992;70:1229-35.

- Toribara N, Sleisenger M. Screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 1995;332:861-7.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to clinical preventative services, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1996.

- Bard J. Colorectal cancer update. Prevention, screening, treatment & surveillance for high risk groups. Med Clin North Am 2000;84:1163-79.

- Wayne M, Cath A, Pamies R. Colorectal cancer: a practical review for the primary care physician. Arch Fam Med 1995;4:357-66.

- Lieberman D, Smith F. Screening asymptomatic subjects for colon malignancy with colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 1991;86:946-51.

- Sinnige H, Mulder N. Colorectal carcinoma: an update. Neth J Med 1991;38:217-28.

- Winawer S, Zauber A, Gerdes H, et al. Risk of colorectal cancer in the families of patients with adenomatous polyps. N Engl J Med 1996;334:82-7.

- Stryker S, Wolff B, Culp C, et al. Natural history of untreated colonic polyps. Gastroenterology 1987;93:1009-13.

- Pennazio M, Arrigoni A, Risio M, Spandre M, Rossini F. Small rectosigmoid polyps as markers of proximal neoplasms. Dis Colon Rectum 1993;36:1121-5.

- Peterson G, Boyd P. Gene tests and counseling for colorectal cancer risk: lessons from familial polyposis. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995;17:67-71.

- Alberts D, Ritenbaugh C, Story J, et al. Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study of effect of wheat bran fiber and calcium on fecal bile acids in patients with resected adenomatous colon polyps. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995;88:81-92.

- Terry P, Giovannucci E, Michels K, et al. Fruit, vegetables, dietary fiber, and risk of colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:525-33.

- Giovannucci E, Rimm E, Ascherio A, Stampfer M, Colditz G, Willett W. Alcohol, low-methionine-low-folate diets, and risk of colon cancer in men. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995;87:265-73.

- Levin K, Dozois R. Epidemiology of large bowel cancer. World J Surg 1991;15:562-7.

- Kune G, Vitetta L. Alcohol consumption and the etiology of colorectal cancer: a review of the scientific evidence from 1957 to 1991. Nutr Cancer 1992;18:97-111.

- Martinez M, McPherson S, Annegers J, Levin B. Cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption as risk factors for colorectal adenomatous polyps. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995;87:274-9.

- Levin B, Murphy G. Revision in American Cancer Society recommendations for the early detection of colorectal cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 1992;42:296-9.

- DeCosse J, Tsioulias G, Jacobson J. Colorectal cancer: detection, treatment and rehabilitation. CA Cancer J Clin 1994;44:27-42.

- Bachwich D, Lichtenstein G, Traber P. Cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Med Clin North Am 1994;78:1399-412.

- Axtell L, Chiazze L. Changing relative frequency of cancers of the colon and rectum in the United States. Cancer 1966;19:750-4.

- Rosato F, Marks G. Changing site distribution patterns of colorectal cancer at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital. Dis Colon Rectum 1981;24:93-5.

- Tedesco F, Wayne J, Avella J, Villalobos M. Diagnostic implications of the spatial distribution of colonic mass lesions (polyps and cancers): a prospective colonoscopic study. Gastroenterol Endosc 1980;26:95-7.

- Cho K, Vogelstein B. Genetic alterations in the adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Cancer 1992;70:1727-31.

- Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1977-83.

- Tomeo CA, Colditz GA, Willet WC, et al. Harvard report on cancer prevention: vol. 3: prevention of colon cancer in the United States. Cancer Causes Control 1999;10:167-80.

- Screening for colorectal cancer-United States, 1997. MMWR 1999;48:116-21.

- Smith R, von Eschenback A, Wender R, Levin B, Byers T, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer: update of early detection guidelines for prostate, colorectal, and endometrial cancers and Update 2001: testing for early lung cancer detection. CA Cancer J Clin 2001;51:38-75.

- Simon J. Occult blood screening for colorectal carcinoma: a critical review. Gastroenterology 1985;88:820-37.

- Van Dam J, Bond J, Sivak M. Fecal occult blood screening for colorectal cancer. Arch Intern Med 1995;155:2389-402.

- Mandel J, Bond J, Church T, et al. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. N Engl J Med 1993;328:1365-71.

- Freedman S. The role of barium enema in detecting colorectal disease: a radiologist's perspective. Postgrad Med 1992;92:245-51.

- Selby J, Friedman G, Quesenberry C, Weiss N. A case-control study of screening sigmoidoscopy and mortality from colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 1992;326:653-7.

- Lieberman D, Weiss D, Bond J, Ahnen D, Garewal H, Chejfec G. Use of colonoscopy to screen asymptomatic adults for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2000;343:162-8.

- Imperiale TF, Wagner DR, Lin CY, et al. Risk of advanced proximal neoplasms in asymptomatic adults according to the distal colorectal findings. N Engl J Med 2000;343:169-74.

- Varma J, Pfenninger J. Flexible sigmoidoscopy. In: Pfenninger J, Fowler G, eds. Procedures for primary care physicians. St. Louis: Mosby, 1994;907-27.

- Barthel J, Hinojosa T, Shah N. Colonoscope length and procedure efficiency. J Clin Gastroenterol 1995;21:30-2.

- Johnson CD, Dachman AH. CT colonography: the next colon screening examination? Radiology 2000;216(2):331-41.

- Deans G, Parks T, Rowlands B, Spence R. Prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 1992;79:608-13.

- Kronborg O. Staging and surgery for colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 1993;29A:575-83.

- Nelson H, Petrelli N, Carlin A, et al. Guidelines 2000 for colon and rectal surgery. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:583-96.

- Abdalla E, Blair E, Jones R, Sue-Ling H, Johnston D. Mechanism of synergy of levamisole and fluorouracil: induction of human leukocyte antigen class I in colorectal cancer cell line. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995;87:489-96.

- Connell MJ, Mailliard JA, Kahn MJ, et al. Controlled trial of fluorouracil and low-dose leucovorin given for 6 months as postoperative adjuvant therapy for colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:246.

- Verschraegen C, Pazdur R. Medical management of colorectal carcinomas. Tumor 1994;80:1-11.

- Winawer S, St. John D, Bond J, et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer: guidelines based on new data. WHO Bull OMS 1995;73:7-10.

- Janne P, Mayer J. Chemoprevention of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1960-8.