Rectal Prolapse and Solitary Rectal Ulcer Syndrome

Rectal prolapse involves the protrusion of the rectum through the anal orifice with procidentia or complete prolapse, which is the common scenario, where all layers of the rectum visibly descend through the anal canal (19). Rectal prolapse can be occult where internal intussusception of the rectal tissue occurs without visible protrusion (2). In mucosal prolapse, the distal rectal tissues and not the entire rectal circumference protrude through the anal orifice.

In adults, rectal prolapse occurs 3 to 10 times more frequently in women, usually in the sixth and seventh decades of life, and is not associated with multiparity. It is often associated with chronic straining of stool, poor tone of the pelvic muscles, fecal incontinence, and occasionally neurologic disease or traumatic damage to the pelvis. Protrusion of the rectal tissue is a striking clinical sign of complete procidentia heralded by the presence of concentric, red, mucosal folds with a palpable double thickness to the rectal wall tissue. Accompanying symptoms include straining with defecation and tenesmus. The rectum may protrude extensively with the lumen tip pointing slightly posteriorly.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy is generally performed to rule out other mucosal lesions such as malignancy or associated solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS). Video defecography is the best way to identify occult prolapse and may show failure of relaxation of the puborectalis muscle, changes in the anorectal angle, and mucosal abnormalities with internal prolapse.

Complete procidentia should be surgically corrected to avoid complications and ongoing damage to the pelvic floor and anal sphincter muscles.

Conservative management with perineal muscle exercises, buttock strapping, and biofeedback training may offer palliation in patients who are unable or refuse to undergo surgery. Surgical management involves the replacement of the rectum into the sacral hollow with or without resection of redundant rectosigmoid colon, which can be carried out with a Ripstein procedure (anterior sling rectopexy).

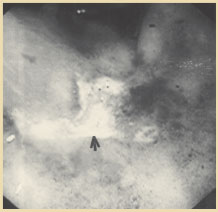

Figure 3. Endoscopic appearance of solitary rectal ulcer in a patient with rectal prolapse. Reprinted with permission from Gopal DV, Young C, Katon RM.

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome presenting with rectal prolapse, severe mucorrhea and eroded polypoid hyperplasia: case report and review of the literature. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15:479 - 483.

This common procedure involves mobilization of the rectum to the tip of the coccyx and attachment of the rectum to the presacral fascia by a nonabsorbable plastic mesh.

SRUS is a benign condition that affects the rectum and usually presents in women during the third and fourth decades of life (19,20). SRUS pursues a chronic course of constipation, mucorrhea-associated rectal prolapse, rectal bleeding, and tenesmus. The etiology of this syndrome is thought to be associated with either overt rectal prolapse or internal intussusception. During defecation, excessive straining forces the anterior rectal mucosa downward against the unyielding pelvic floor, causing trauma and focal ischemia to the mucosa.

Approximately one quarter of all patients with SRUS are incorrectly diagnosed at the initial assessment, proving that this syndrome can be easily missed if specific details of medical history, clinical course, and physical examination are not noted.

Once clinical symptoms are elucidated and flexible sigmoidoscopy is performed (Figure 3), other investigations are rarely required and have a limited value in confirming SRUS.

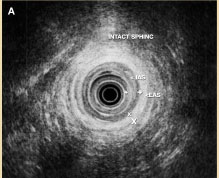

Figure 4A. Intact internal anal sphincters (IAS) and external anal sphincters (EAS).

Figure 4A. Intact internal anal sphincters (IAS) and external anal sphincters (EAS).

Occasionally, a barium enema may show nodularity of the rectal mucosa and thickening of the first valve of Houston, but ulceration is not often demonstrated, and in 40% to 50% of cases the study is normal.

Management of SRUS is based on the presence of symptoms. Usually conservative therapy with bulk laxatives and bowel retraining is attempted before considering surgical options for intractable or worsening symptoms. Medical management can include the application of local steroids or 5-acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) products.

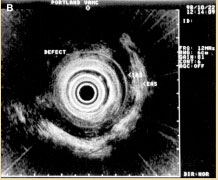

Figure 4B. Anterior IAS and EAS anal sphincter injury. Reprinted with permission from Gopal DV, Faigel DO. Rectal endoscopic ultrasound - a review of clinical applications. Endoscopic ultrasonography and therapeutic indications. Series #2. Pract Gastroenterol. 2000;24:24 - 34.

Figure 4B. Anterior IAS and EAS anal sphincter injury. Reprinted with permission from Gopal DV, Faigel DO. Rectal endoscopic ultrasound - a review of clinical applications. Endoscopic ultrasonography and therapeutic indications. Series #2. Pract Gastroenterol. 2000;24:24 - 34.

Although these have been unsuccessful in treating the underlying defecatory disorder, macroscopic healing does occur. Dietary treatment with fiber and bulk-forming agents is often recommended, but there is little evidence to support this approach. Because some patients may have a predominant behavioral disorder of excessive straining with defecation, biofeedback and retraining may show some benefit. Biofeedback typically includes correction of the pelvic floor defecatory behavior; regulation of toilet habits; encouragement to stop the use of laxatives, suppositories, and enemas; and discussion of any psychosocial factors that may contribute to the behavior.

It is often used in adjunct with surgery and has demonstrated successful results in case series with limited long-term follow-up.

Deepak V. Gopal, MD, FRCP (C)

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Division of Gastroenterology

Oregon Health & Science University

Portland VA Medical Center

Portland, Oregon

REFERENCES

1. Schrock TR. Examination and diseases of the anorectum. In: Feldman M, Scharschmidt BF, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease.

2. Barnett JL. Anorectal diseases. In: Yamada T, Alpers DH, Laine L, et al, eds. Textbook of Gastroenterology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:2083 - 2107.

3. Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A. The prevalence of hemorrhoids and chronic constipation: an epidemiological study. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:380 - 386.

4. Breen E, Bleday R. Clinical features of hemorrhoids. [UpToDate Clinical Reference on CD-ROM & Online Web site.] December 2001.

5. Haas PA, Fox TA, Haas G. The pathogenesis of hemorrhoids. Dis Colon Rectum. 1984;27:442 - 450.

6. Bleday R, Breen E. Treatment of hemorrhoids. [UpToDate Clinical Reference on CD-ROM & Online Web site.] December 2001.

7. MacRae HM, McLeod RS. Comparison of hemorrhoidal treatments: a meta-analysis. Can J Surg. 1997;40:14 - 17.

8. Reis Neto JA, Quilici FA, Cordeiro F, Reis JA. Open versus semi-open hemorrhoidectomy: a random trial. Int Surg. 1992;77:84 - 90.

9. Khubchandani M. Results of Whitehead operation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1984;27:730 - 732.

10. Breen E, Bleday R. Anal fissures. [UpToDate Clinical Reference on CD-ROM & Online Web site.] December 2001.

11. Lund JN, Scholefield JH. Aetiology and treatment of anal fissure. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1335 - 1344.

12. Shub HA, Salvati EP, Rubin RJ. Conservative treatment of anal fissure: an unselected, retrospective, and continuous study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1978;21: 582 - 583.

13. Brisinda G, Maria G, Bentivoglio AR, et al. A comparison of injections of botulinum toxin and topical nitroglycerin ointment for the treatment of chronic anal fissure. N Engl J Med. 1999; 341:65 - 69.

14. Cook TA, Humphreys MM, McC Mortensen NJ. Oral nifedipine reduces resting anal pressure and heals chronic anal fissure. Br J Surg. 1999;86: 1269 - 1273.

15. Lewis TH, Corman ML, Prager ED, Robertson WG. Long-term results of open and closed sphincterotomy for anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31: 368 - 371.

16. Breen E, Bleday R. Anal abscesses and fistulas. [UpToDate Clinical Reference on CD-ROM & Online Web site.] December 2001.

17. Nordgren S, Fasth S, Hulten L. Anal fistulas in Crohn's disease: incidence and outcome of surgical treatment. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1992;7:214 - 218.

18. Venkatesh KS, Ramanujam P. Fibrin glue application in the treatment of recurrent anorectal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1136 - 1139.

19. Gopal DV, Young C, Katon RM. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome presenting with rectal prolapse, severe mucorrhea, and eroded polypoid hyperplasia: case report and review of the literature. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15:479 - 483.

20. Mackle EJ, Parks TG. The pathogenesis and patho-physiology of rectal prolapse and solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;15: 985 - 1001.

21. Gopal DV, Faigel DO. Rectal endoscopic ultrasound - a review of clinical applications. Endoscopic ultrasonography and therapeutic indications. Series #2. Pract Gastroenterol. 2000;24:24 - 34.

22. Robson K, Lembo AJ. Fecal incontinence. Chopra S, La Mont T, eds. [UpToDate Clinical Reference on CD-ROM & Online Web site.] December 2001.

23. Nostrant TT. Radiation injury. In: Yamada T, Alpers DH, Laine L, et al, eds. Textbook of Gastroenterology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:2611 - 2612.

24. Swaroop VS, Gostout CJ. Endoscopic treatment of chronic radiation proctopathy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:36 - 40.

25. Bonis P, Breen E, Bleday R. Approach to the patient with anal pruritus. [UpToDate Clinical Reference on CD-ROM & Online Web site.] December 2001.

26. American Joint Committee on Cancer. Manual for Staging of Cancer. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: JB Lippincott; 1992:75 - 79.

27. Magdeburg B, Fried M, Meyenberger C. Endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis, staging, and follow-up of anal carcinomas. Endoscopy. 1999;31:359 - 364.