Schizophrenia Psychological Treatments

Many patients must try a variety of medications before finding one that controls their symptoms. This can be a very difficult and frustrating process. Many months or years may pass before a patient begins to get relief from his or her symptoms and accept the medication’s side effects. To help make this process easier, many people with schizophrenia benefit from therapy, family support, a community-based rehabilitation program, or some combination of the three. Psychological treatments include individual psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and social skills training.

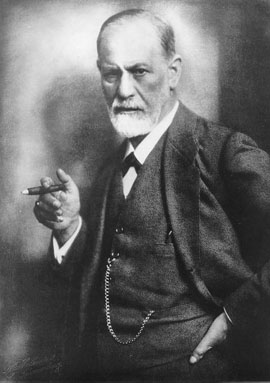

Sigmund Freud created psychoanalysis, a philosophy in which symptoms of mental illness are considered external expressions of unconscious problems. In psychoanalysis, an analyst and patient meet frequently to reveal and explore these unconscious conflicts. Psychoanalysis is hard work for both patient and therapist. In the first half of the twentieth century, patients with schizophrenia were routinely treated with psychoanalysis.

Psychotic patients were asked to discuss their symptoms and consider them in relation to their childhood experience—an exhausting and potentially impossible task. In the 1980s, researchers began to reveal that not only was psychoanalysis not helpful for patients with schizophrenia, but also, in some cases, it actually made people worse. Researchers suspect that the stress of a psychoanalytic session was simply too much for many patients with schizophrenia to handle.

More recently, therapists have begun to use personal therapy to treat schizophrenia. Personal therapy is another form of individual psychotherapy in which patients work one-on-one with a therapist to learn coping and life skills. Different skills are taught at appropriate stages of a patient’s recovery. For example, when a patient is just coming home from the hospital, a therapy session might focus on identifying and managing stress. Later, a patient might learn how to talk about a problem with a family member.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Many mental disorders are characterized by thoughts and behaviors that make people unhappy or uncomfortable. People who are depressed often think negatively about themselves and believe that they are worthless.

Figure 5.3 Sigmund Freud created psychoanalysis, an ineffective treatment for schizophrenia. National Library of Medicine

Figure 5.3 Sigmund Freud created psychoanalysis, an ineffective treatment for schizophrenia. National Library of Medicine

As you have learned, many schizophrenia patients experience delusions, or false beliefs that are resistant to change. The goal of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is to change these maladaptive thoughts and behaviors.

In the past, CBT was used primarily to treat depression and anxiety disorders. Clinicians thought schizophrenic patients were too impaired to be treated with CBT. Recently, researchers in the United Kingdom have explored the use of CBT with schizophrenia patients. Therapists challenge the reality of hallucinations and delusions and ask patients to consider alternative explanations for their strange experiences. The goal of this process is to decrease the impact of symptoms, keep patients out of the hospital, and improve their social interactions. Because this is such a new treatment for schizophrenia, there is little research to tell us how helpful it is. One study has shown that schizophrenia patients who undergo CBT report that their symptoms improve. Studies have also found, however, that other types of therapy are equally effective. Researchers wonder whether the type of therapy is less important than the emotional support therapy in general provides.

Heather Barnett Veague, Ph.D.

Heather Barnett Veague attended the University of California, Los Angeles,

and received her Ph.D. in psychology from Harvard University in 2004. She

is the author of several journal articles investigating information processing

and the self in borderline personality disorder. Currently, she is the Director

of Clinical Research for the Laboratory of Adolescent Sciences at Vassar

College. Dr. Veague lives in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, with her husband

and children.

References