Alzheimer Disease: From Clinical Description to a Theory of Disease and Treatment

The story of Alzheimer disease began with a series of clinical observations that were linked to a type of brain pathology. These clinical and pathological observations have led to theories of pathophysiology, which in turn have pointed to possible pathways to treatment. The time from disease recognition to the first symptomatic treatment was nearly 90 years. Treatments aimed at altering the disease process are still in development.

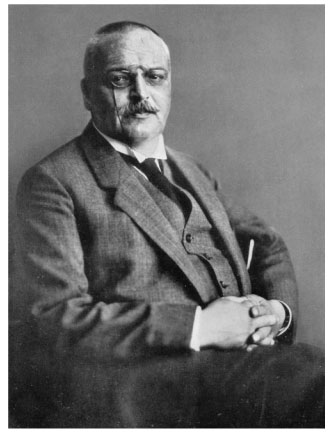

The story began on April 8, 1906, when psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer (Figure 1-1) examined the brain of Auguste D, a woman who at age 51 years had been admitted, on November 25, 1901, to the Hospital for the Mentally Ill and Epileptics in Frankfurt, Germany. Her family physician’s admittance note indicated that she had been suffering for a long time from weakness of memory, persecution mania, sleeplessness, and restlessness and that she was no longer able to do any physical or mental work.

Alzheimer had seen her at the Frankfurt facility, but in 1903 had joined Emil Kraepelin at the Royal Psychiatric Clinic in Munich, where Alzheimer became head of the Anatomical Laboratory (Figure 1-2) (Goedert and Spillantini 2006).

It was here that Alzheimer received the woman’s brain following her death. Grossly, he noted brain shrinkage and mild hydrocephalus ex vacuo. On applying the recently developed Bielchowsky silver stain to brain slides, he noted fibrils that stained differently from normal neurofibrils and millet seed-sized lesions containing a peculiar substance distributed throughout the outer layers of the entire cerebral cortex.

His findings were published in 1907 (Alzheimer 1907/1987); he thought the disease was a rare form of presenile dementia. By 1908, Alzheimer and his colleague Perusini had found a total of four cases of presenile dementia, all of whom had similar pathology (Maurer 2006). Only 2 years later, Kraepelin (1910) (Figure 1-3) included the eponym Alzheimer’s disease in his textbook of psychiatry. Despite the fact that both plaques and tangles had been described earlier by other investigators (Drachman 2006b), the name stuck.

Belying the paucity of references in PubMed cited earlier, there was a lively discussion in the literature of the 1920s and 1930s concerning the clinical signs and symptoms of Alzheimer disease, the relationship of histopathology to clinical symptoms, and the relationship of Alzheimer disease to senile dementia (reviewed in Newton 1948).

FIGURE 1-1. Alois Alzheimer, M.D.

FIGURE 1-1. Alois Alzheimer, M.D.

Source. Department of Psychiatry, Ludwig Maximilian University Munich.

However, it did not become widely accepted that Alzheimer-type change in brain had a strong relationship to senile-onset dementia until the work of British pathologist J.A. N. Corsellis (1962). Corsellis performed postmortem studies of the brains of institutionalized persons with diagnoses such as schizophrenia, affective disorders, and paranoid disorders and compared them with the brains of persons having diagnoses of senile dementia or mixed senile/vascular dementia, but not with those of persons diagnosed clinically with other brain diseases. He found that 80% of the senile dementia group showed moderate to severe plaque formation.

Patients with psychiatric diagnoses had only moderate to severe plaque formation if they lived to be age 75 years or older. Neurofibrillary tangles occurred almost exclusively in persons diagnosed with senile and mixed senile/vascular dementia. These tangles tended to parallel the plaque density, and their frequency was not related to patient age. In the same year, Kay (1962) noted that a diagnosis of senile dementia was associated with markedly reduced life expectancy.

Sim and Sussman (1962) published the course of 21 cases of biopsy-proven and neuropathologically proven Alzheimer disease. They still considered the disease to be a presenile dementia, although Simchowitz, who first used the term senile plaque and had also described granulovacuolar degeneration, had written in 1914 that there was no difference between Alzheimer disease and senile dementia (Simchowitz 1914). Sim and Sussman compared the clinical picture of persons seen in years 1-4 of symptoms.

FIGURE 1-2. Alzheimer laboratory in Munich.

FIGURE 1-2. Alzheimer laboratory in Munich.

Source. Department of Psychiatry, Ludwig Maximilian University Munich.

They found amnesia and disorientation to be the earliest symptoms, dysphasia as intermediate, and apraxia and manifest dementia to occur later. They noted that in the early stages, despite poor orientation and memory loss, patients were not demented and were able to organize themselves and their environment to a remarkable degree, evidencing what we might now call mild cognitive impairment according to the criteria developed by Petersen et al. (1999).

The work of Sim and Sussman also set the stage for the later development by Rosen et al. (1984) of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale, which became one of the two standard assessment instruments in subsequent clinical trials of medication for Alzheimer disease. In 1963, electron microscopy showed that neurofibrillary tangles consisted of paired helical filaments (Kidd 1963). Three years later, Roth et al. (1966) examined the brains of patients ages 60 years and older who had been seen in a psychiatric or general hospital, had been evaluated cognitively, and did not have evidence of stroke. He came to the following three conclusions: