Weight Loss Seems to Spare Knee Cartilage

The loss of 10% of body weight slowed degeneration of knee cartilage among overweight or obese patients, researchers reported here.

In a retrospective imaging study, those who lost more weight had a greater reduction in the rate of cartilage layer damage as measured by T2 on MRI, Alexandra Gersing, MD, of the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), and colleagues reported at the Radiological Society of North America meeting.

“Substantial weight loss not only slows knee joint degeneration, it also reduces the risk of developing osteoarthritis,” Gersing said. “The studies show there is a protective aspect of weight loss on knee cartilage. Weight loss may slow or prevent osteoarthritis.”

Gersing and colleagues assessed 506 patients who were enrolled in the Osteoarthritis Initiative. The mean age was 62, 60% were women, and the average body mass index was 30.2 kg/m2.

During the 4-year study, 177 patients lost between 5% and 10% of their body weight and 76 patients lost more than 10% of body weight. The 253 patients who didn’t lose weight served as controls.

The researchers used T2 relaxation time measurements from MRI in order to see changes in cartilage quality at an early stage, before it breaks down, Gersing said. Less T2 increase translates to less cartilage degeneration, she explained.

They found that those who lost more weight had less cartilage damage over time. Patients who didn’t lose weight had a 0.9-point increase in T2 measurements over 4 years, and those who lost 5% to 10% of their body weight had about the same increase.

But those who lost at least 10% of their body weight had an increase of less than 0.4 points in T2 score, for a 55.6% reduction in the rate of cartilage layer damage, Gersing said.

But those who lost at least 10% of their body weight had an increase of less than 0.4 points in T2 score, for a 55.6% reduction in the rate of cartilage layer damage, Gersing said.

The effect of weight loss was even more pronounced when looking specifically at media tibia cartilage. The T2 increase among those who did not lose weight was 1.1 points over 4 years, and it was about 0.8 points among those who lost 5% to 10% of their body weight.

However, it rose barely 0.1 points from baseline among those who shed at least 10% of their body weight, for a reduction of 90.8% in the rate of degenerative changes, they reported.

Weight loss also correlated with knee pain, they found. Knee pain based on the Western Ontario & McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) increased slightly in patients who did not lose weight, while it fell about 2.5 points among patients who lost 5% to 10% of body weight and dropped 0.9 points in those who lost more than 10% of body weight.

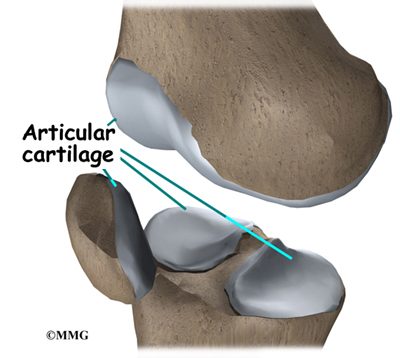

“Degenerative joint disease is a major cause of pain and disability in our population, and obesity is a significant risk factor,” Gersing said. “Once cartilage is lost in osteoarthritis, the disease cannot be reversed.”

Although the findings are retrospective, they still may offer enough information so doctors can again try to persuade overweight patients about the benefits of shedding excess pounds, said Salomao Faintuch, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, who wasn’t involved in the study.

“Even though we like prospective studies better to provide scientific evidence, the retrospective design is not really a problem in this study,” he said. “It is obvious and well known that losing weight helps people in so many different ways. The real novelty of this study is showing that how much weight you lose really makes a difference. Losing a little bit can make things better, losing even more makes it even better than that.”

“It is important to be able to quantify that,” he added. “If you lose weight, your joints are going to do better.”

Future research by Gersing and colleagues will include the role of diabetes in cartilage degeneration, according to a UCSF news release.

###

Primary Source

Radiological Society of North America