Schizophrenia Typical & Atypical Antipsychotic Medication

Typical Antipsychotic Medication

The first medications designed to treat schizophrenia are now called typical antipsychotic medications, or first-generation antipsychotics. Many of these early medications are still used today, and are helpful for many patients. Some examples of these medications are chlorpromazine and haloperidol. Typical antipsychotic medications work by blocking the effects of dopamine. Because of this primary function, some call these medications neuroleptics, which literally means “seizing the neuron.”

Typical antipsychotic medications are most effective in treating positive symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions. Although some patients may improve after only a week or two of treatment, the most complete effects of these medications are usually seen after six to eight weeks. Unfortunately, treatment with typical antipsychotic medications does cause some uncomfortable side effects. Many patients experience significant weight gain, drowsiness, or dry mouth. Some patients experience extra-pyramidal side effects (EPS), which are uncontrollable bodily movements such as muscle spasms or shaking. Other medications can be used to minimize extrapyramidal side effects, although the relief is only temporary.

In fact, studies have shown that patients who take typical antipsychotic medications for 10 years or more may develop a serious condition called tardive dyskinesia in which patients experience involuntary movements of the tongue, lips, and neck. Tardive dyskinesia is very uncomfortable and can be embarrassing to many patients.

Atypical Antipsychotic Medication

Although the typical antipsychotic medications are effective in treating positive symptoms, they are relatively unsuccessful in treating negative symptoms. Additionally, these medications cause unpleasant side effects. In the 1980s, researchers focused on developing medications that treated more aspects of schizophrenia and did so without disabling side effects. These medications that are used frequently today are called atypical antipsychotic medications, or second-generation antipsychotics.

Clozapine was the first atypical antipsychotic and was designed to help patients who did not respond well to traditional neuroleptics. It became available in the United States in 1989 and now is prescribed widely by psychiatrists. Newer atypical antipsychotic medications include risperidone and olanzapine. These medications provide relief for patients without the uncomfortable side effects. Unlike early antipsychotic medications, atypical antipsychotic medications are effective at treating both positive and negative symptoms.

How do these medications differ from earlier medications?

Researchers speculate that traditional antipsychotic medications completely block one kind of dopamine receptor, leaving other types of dopamine receptors unaffected. Atypical antipsychotics appear to block many kinds of dopamine receptors less completely.

-

John Hinckley Jr.

John Hinckley Jr. was, by all accounts, a normal child. Born

to successful and wealthy parents, John was the youngest of

three children. His mother doted on him and remembers him

being quiet and introspective. In high school, John spent most

of his time alone in his room, playing his guitar and listening

to the Beatles. Although his parents attributed his isolation to

shyness, high school classmates recall that he was odd and

a loner.

After high school, John completed a year of college in Texas

before dropping out to pursue his dream of becoming a song-

writer. He moved to Hollywood, found an apartment, and worked

on his music. While in California, he watched the movie Taxi

Driver more than 15 times. He became obsessed with the story

of an American recluse who stalks a political candidate.

In 1979, John Hinckley bought his first gun, which was to

become part of a collection. Personal photographs reveal him

holding a gun to his temple on two occasions. According to

later reports, John played Russian roulette twice shortly after

he acquired his first handgun. By 1980, John was experienc-

ing more symptoms of mental illness. He began treatment with

antidepressants and tranquilizers. Despite his psychiatric prob-

lems, John continued to add to his gun collection.

In May of 1980, John Hinckley read an article in People maga-

zine about the actress Jodie Foster. In the article, he learned that

the actress was enrolled at Yale. Hinckley was impressed by Foster

because of her role in Taxi Driver. He decided to enroll in a writing

course at Yale so that he could be close to her. While there, John

tried to establish a relationship with the actress. He wrote her let-

ters and poems and left them for her in her mailbox. Because his

attempts at making contact with her were largely unsuccessful,

he decided to try something different to get her attention.

John Hinckley believed that by assassinating the president, he could

obtain Jodie Foster’s love and devotion. On Monday, March 30,

1981, John wrote a letter to Jodie Foster describing his plan to

assassinate President Reagan. He went to Washington, D.C., and

checked into a hotel. In the afternoon, he left his hotel room and

took a cab to the Washington Hilton, where President Ronald

Reagan was to speak to a labor convention.

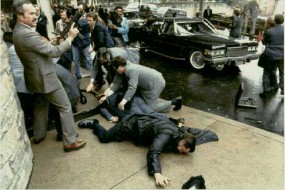

Figure 5.2 Would-be assassin John Hinckley is wrestled to

Figure 5.2 Would-be assassin John Hinckley is wrestled to

the ground after his attempt on President Reagan’s life.

At 1:30 p.m., John fired six shots. The bullets from Hinckley’s

gun struck Ronald Reagan in the chest, Reagan press secretary

James Brady in the temple, police officer Thomas Delahanty in

the neck, and Secret Service agent Timothy J. McCarthy in the

stomach. Hinckley was immediately arrested and was tried for

his crime a year later. On June 21, 1982, after seven weeks

of testimony and three days of deliberation by the jury, John

Hinckley was found not guilty by reason of insanity. He currently

lives at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, D.C., where he

is treated for schizophrenia.

—

This may help alleviate all types of schizophrenia symptoms but not cause the movement disorders associated with typical medications.

Unfortunately, there are side effects associated with atypical antipsychotic medications. Like the earlier medications, atypical medications can cause drowsiness and weight gain. In very rare cases, clozapine can cause a blood disorder called agranulocytosis. In order to prevent this condition, patients taking clozapine must take weekly blood tests to monitor their blood count.

Heather Barnett Veague, Ph.D.

Heather Barnett Veague attended the University of California, Los Angeles,

and received her Ph.D. in psychology from Harvard University in 2004. She

is the author of several journal articles investigating information processing

and the self in borderline personality disorder. Currently, she is the Director

of Clinical Research for the Laboratory of Adolescent Sciences at Vassar

College. Dr. Veague lives in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, with her husband

and children.

References