Discussing Bone Health

Healthy puberty brings about a growth spurt. Young people who develop anorexia before reaching their genetically programmed adult height may end up shorter than they would be if they were nutritionally healthy. Boys grow for about two years longer than girls and thus are more prone to shortened stature as a result of anorexia. Through improved nutrition, these individuals are often able to make up for some of their lost growth, but they may never reach their full height potential. Semistarvation disturbs the body’s hormone system. A hallmark of anorexia nervosa, amenorrhea (the absence of menstrual periods) stems from a combination of poor nutrition, reduced body fat, overexercise, low weight, and emotional stress. Insufficient body fat, in particular, is an important reason why girls with anorexia nervosa do not get their periods.

If your daughter’s anorexia begins prior to or early in puberty, her first menstrual period and the development of other features of sexual maturity will likely be delayed. If she falls prey to anorexia after menarche (first menses), she will find that her monthly cycles become irregular or stop.

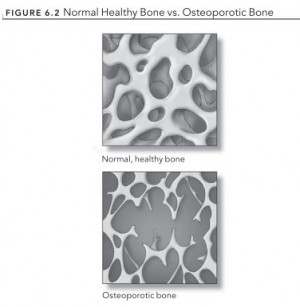

Amenorrhea and low estrogen set the stage for bone loss, a condition known as osteopenia, which can develop early in the course of anorexia and advance to the more serious condition of osteoporosis. More than 90 percent of women and 50 percent of teenage girls with anorexia sustain some loss in bone density. As a result, their bones become fragile, weak, and particularly susceptible to fracture. Due to a combination of bone loss and inadequate bone formation, people who develop anorexia during adolescence are more vulnerable to osteoporosis than those who develop the eating disorder later in life.

Bone loss occurs in many boys with anorexia as well. The good news is that advances in x-ray technology have made it possible to detect bone loss (or risk thereof ) in its early stages. Painless, noninvasive, and with minimal radiation, a bone density test (also known as densitometry) measures the amount of mineral in a bone. The skeletal areas most often tested are the lower spine (lumbar vertebrae) and the hips. Higher density bones are stronger and more resistant to breakage than lower density ones. Looking back on her initial bone density study, Anita notes, “It was really easy and fast. Less than a year after the first test, my doctor recommended a second one to see if there were any changes.” The suggested interval of not more than a year between a first and second bone density scan is particularly important in the teenage years, which represent a key period of growth. Bone formation is greatest between the ages of 11 and 14 in girls and 13 and 16 in boys. Ninety percent of a person’s total bone mass has developed by late adolescence or early adulthood.

For a girl to bring back her periods, she needs to regain weight, with a healthy proportion of it consisting of fat. The patient with anorexia who overexercises is often very anxious about putting on pounds in the form of fat. She may regain the suggested amount of weight, but because not enough of it is fat, a delay in the return of her periods is possible. It is not unusual for an individual to perceive thinness as more important than the restart of her menses, especially if she competes in a sport that ties weight to performance. If your daughter is reluctant to put on fat, you need to be patient, realizing how emotionally charged this topic is for her.

Offer her empathy with statements such as “It took a lot of courage and hard work to meet your weight goal, and you’ve done a tremendous job. Now that you’ve regained the weight, it must be so difficult to hear that your body fat is too low.” It’s a good policy to link discussion of body size and shape to health and safety. Thus, gently remind her that the body requires a certain amount of fat to maintain its hormone system, which in turn helps keep bones strong and resistant to injury.

FIGURE 6.2 Normal Healthy Bone vs. Osteoporotic Bone

FIGURE 6.2 Normal Healthy Bone vs. Osteoporotic Bone

When an individual with anorexia regains a healthy nutritional state, her bone density increases but-at least in the short termdoesn’t recover completely from its loss. Girls with anorexia need to take in about 1,300 to 1,500 milligrams of calcium (a key component of bones), as well as 400 international units (IU) of vitamin D daily. Vitamin D helps the body absorb calcium. Because girls with osteoporosis are particularly vulnerable to fracture, it is important for them to avoid high-impact sports. You have probably read that exercise is thought to increase bone density; while this is generally the case, it does not hold true for individuals with anorexia nervosa. Muscle and fat tissues, as well as a normal menstrual cycle, play a major role in the growth of strong bones. When teenage girls with anorexia overexercise, their supplies of muscle and fat decrease, and this might further hamper bone formation.